Common Fluid Mechanics Questions & Answers

Jan 18, 2026

Deepak S Choudhary

🔧 Trusted by 23,000+ Happy Learners

Industry-Ready Skills for Mechanical Engineers

Upskill with 40+ courses in Design/CAD, Simulation, FEA/CFD, Manufacturing, Robotics & Industry 4.0.

Fluid mechanics explains how liquids and gases move, exchange pressure and velocity, and lose energy through friction. This interview-focused guide covers laminar vs turbulent flow, Reynolds number, continuity equation, Bernoulli’s principle, head loss, boundary layers, cavitation, pumps and turbines, viscosity, and manometers with simple engineer-first interpretations.

Fluid mechanics studies how fluids behave at rest and in motion. In simple terms, it connects pressure, velocity, elevation, and losses so you can predict what a flow system will actually do.

Have you ever seen a pressure drop that “should not happen,” a pump that sounds like gravel, or a flow rate that refuses to match the calculation?

This guide answers the exact verbal questions interviewers ask, across flow regimes, Bernoulli and continuity, pipe losses, boundary layer behavior, cavitation, pumps and turbines, and practical pressure measurement with manometers, using short explanations and small examples.

Fluid Properties And Flow Regimes

Q1. What is viscosity?

Viscosity is a fluid’s internal resistance to shear, meaning how strongly it resists layers sliding past each other.

Water has low viscosity, so it flows easily, while oil has higher viscosity,y so it “drags” more under the same shear.

Q2. What is the difference between dynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity?

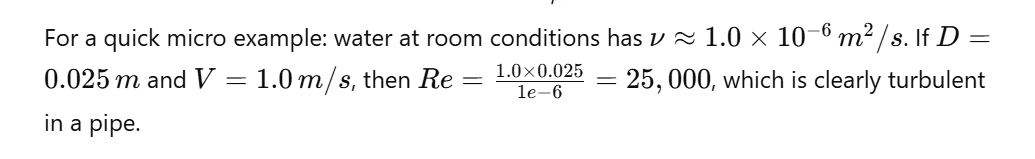

Dynamic viscosity, μ, measures shear resistance directly. Kinematic viscosity, ν, is μ divided by density, so it captures how easily momentum diffuses through the fluid relative to density. In practice, ν is convenient for Reynolds number work because it bundles μ and ρ into one property.

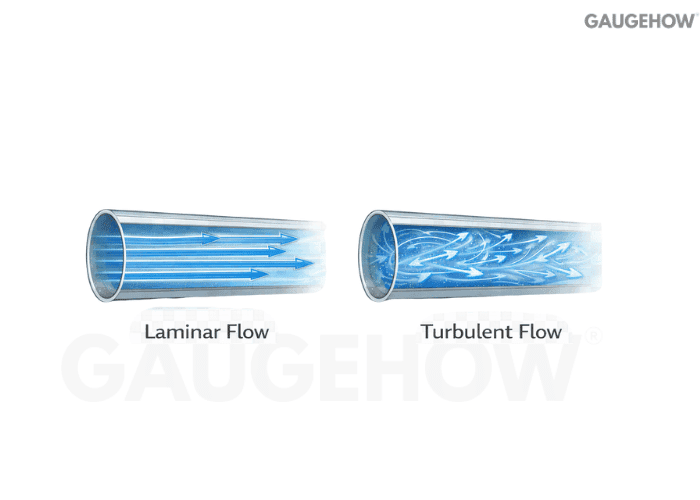

Q3. What is laminar flow?

Laminar flow means fluid layers move in an orderly way with minimal cross-mixing. Viscous effects dominate, so velocity changes smoothly from the wall to the center.

Q4. What is turbulent flow?

Turbulent flow has strong mixing and random velocity fluctuations. Inertia dominates, eddies form across a range of sizes, and losses rise sharply compared to laminar flow.

Q5. Why do engineers care about laminar vs turbulent flow?

Because the regime controls pressure drop, mixing, heat transfer, and the reliability of “textbook” assumptions. A design that is stable in laminar flow can become noisy, lossy, or unpredictable once it transitions to turbulence.

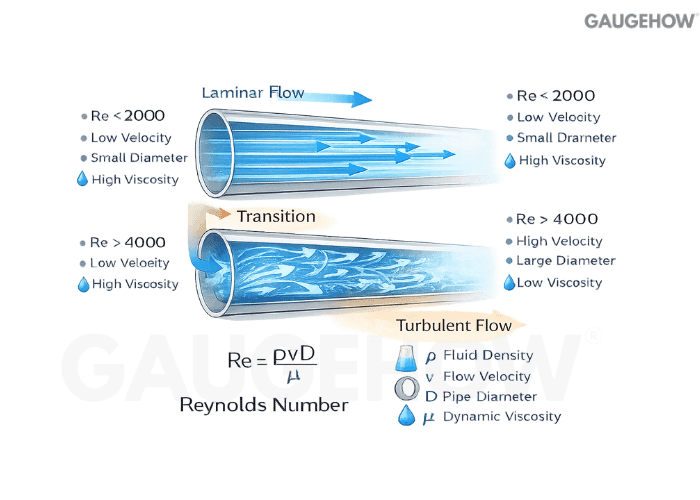

Q6. What is the Reynolds number?

Reynolds number is a dimensionless ratio of inertia effects to viscous effects. It tells you which physics dominates the flow, which is why it is the first checkpoint for deciding laminar, transitional, or turbulent behavior.

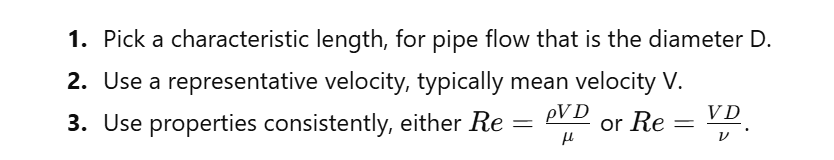

Q7. How do you calculate reynolds number?

You compute it from a representative velocity, a characteristic length, and fluid properties.

Q8. What Reynolds number is turbulent in a circular pipe?

As a working rule, laminar is below about 2300, transition is roughly 2300 to 4000, and turbulent is above about 4000. Surface roughness and disturbances can shift the transition earlier, so treat it as a guideline, not a guarantee.

Continuity And Bernoulli

Q9. What is the continuity equation?

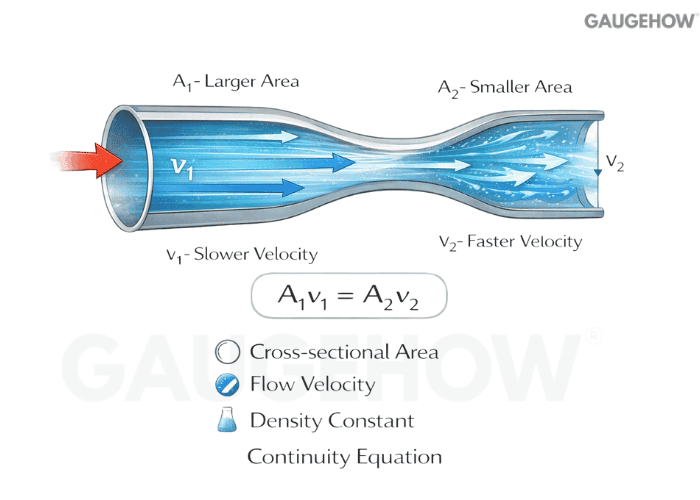

Continuity is the conservation of mass. It says mass flow in equals mass flow out unless mass accumulates inside the control volume.

Q10. When does continuity simplify to

That simplified form applies to steady, incompressible flow in a duct or pipe with no leakage and no storage. If density changes meaningfully, use the mass form pAV.

Q11. What is Q in fluid mechanics?

Q typically denotes volumetric flow rate. In a full pipe, it is

area times average velocity.

Q12. What is the Bernoulli effect?

The Bernoulli effect is the practical observation that when flow speed increases, static pressure tends to drop, provided losses and energy addition are negligible. Engineers use it as an energy bookkeeping idea, not as a “suction explanation.”

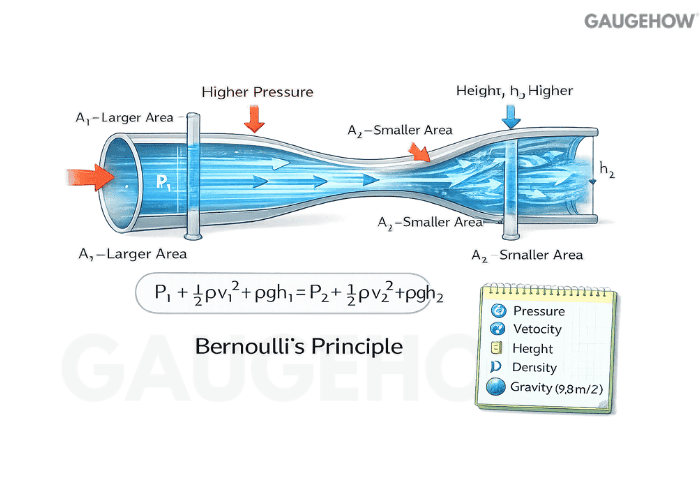

Q13. What is Bernoulli’s equation?

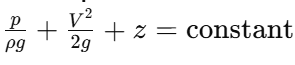

A common form along a streamline is

Those terms represent pressure head, velocity head, and elevation head. Physically, it is how total mechanical energy per unit weight is distributed between pressure, motion, and height.

Q14. How to derive Bernoulli’s equation?

In interview terms, the derivation is an energy balance under a tight set of assumptions.

Start from the steady flow momentum/energy idea along a streamline.

Assume incompressible flow and negligible viscosity, so no mechanical energy is dissipated as heat.

Exclude pumps and turbines, so no shaft work is added or extracted.

Integrate along the streamline to show that pressure energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy sum to a constant:

The key is not the math. The key is stating the assumptions and knowing what breaks them.

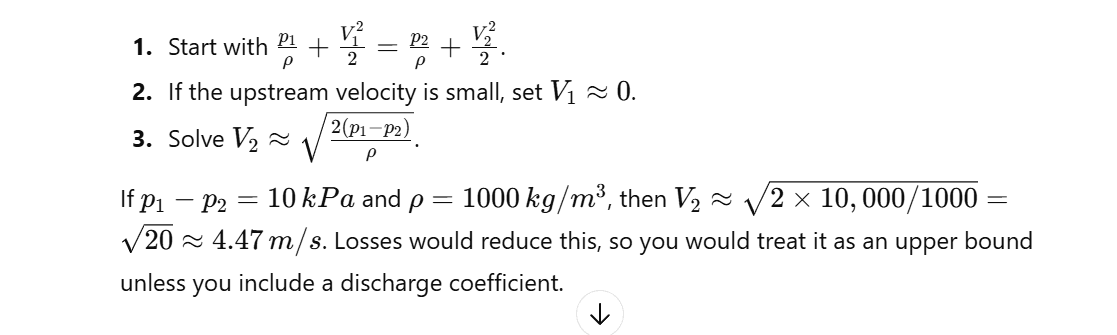

Q15. Give a micro example of Bernoulli used the right way.

A clean use case is estimating a jet speed from a pressure difference when the elevation change is negligible.

Head Losses In Pipes

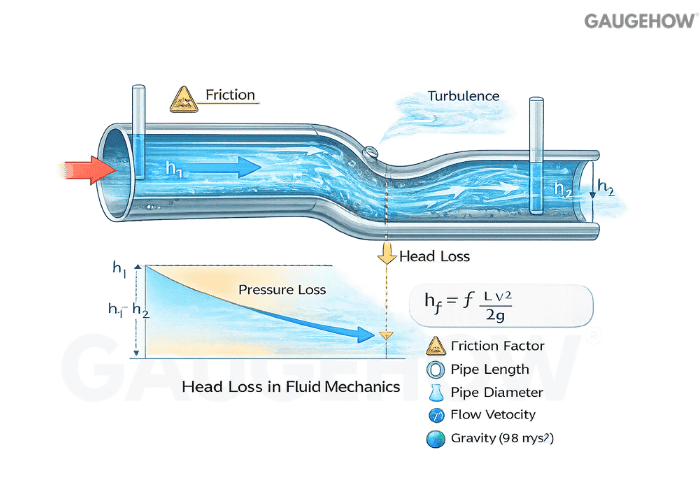

Q16. What is head loss in fluid mechanics?

Head loss is the energy per unit weight dissipated by friction and mixing. It shows up as a drop in total head between two points.

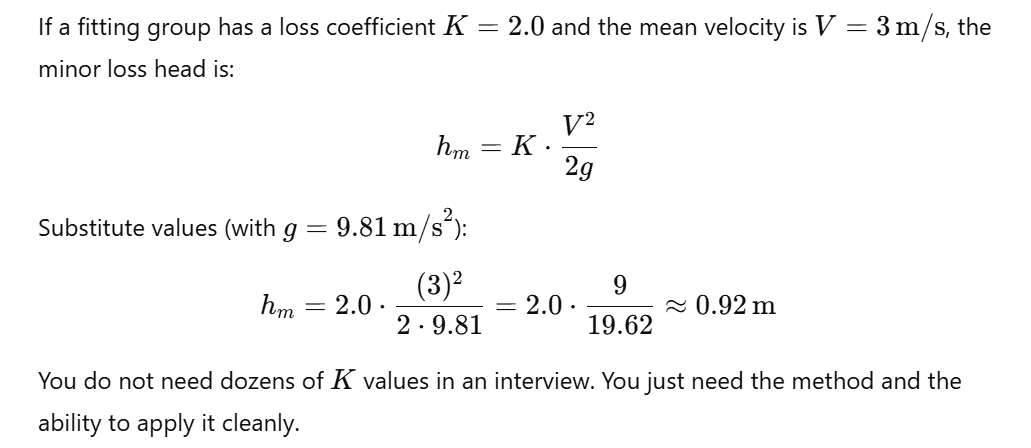

Q17. What is the difference between major losses and minor losses?

Major losses come from wall friction over length, commonly handled by Darcy–Weisbach. Minor losses come from components and geometry changes like bends, valves, entrances, expansions, and contractions.

Micro example:

Q18. How do you calculate friction head loss using Darcy–Weisbach?

Darcy–Weisbach is the workhorse for full-pipe friction:

Compute mean velocity

Q19. How do you estimate the friction factor in laminar versus turbulent flow?

In fully developed laminar pipe flow, the friction factor follows a simple inverse Reynolds relationship, and roughness is not the driver. In turbulent flow, f depends on both Reynolds number and relative roughness, which is why rough pipes behave very differently at the same flow rate.

Q20. What is hydraulic diameter, and when do you use it?

Hydraulic diameter lets you use pipe-style Reynolds number and loss correlations for non-circular ducts such as rectangular passages, annuli, and other internal channels. It is an “equivalent length scale” for internal flow calculations.

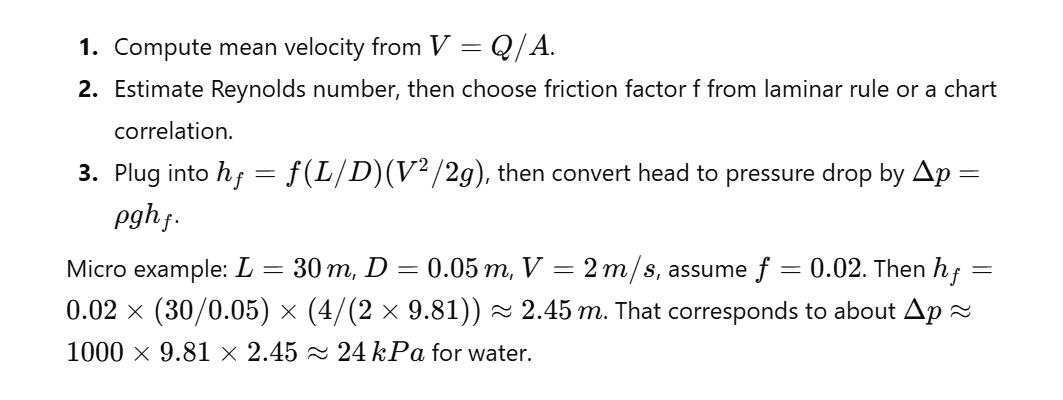

Boundary Layer And Separation

Q21. What is a boundary layer?

The boundary layer is the thin region near a wall where viscosity strongly matters. Velocity rises from zero at the wall to near free-stream value across a small thickness.

Q22. What causes a boundary layer to develop?

No-slip at the wall forces velocity to be zero at the surface, so shear forms and momentum diffuses outward. That diffusion creates a velocity gradient region, which we call the boundary layer.

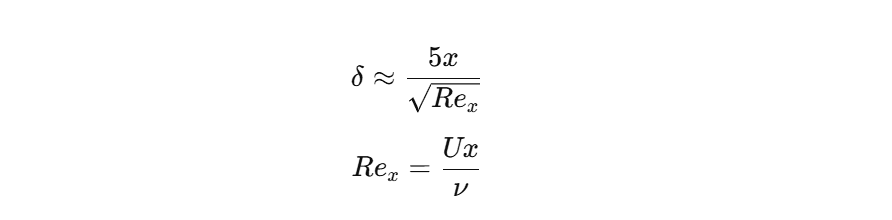

Q23. How to calculate boundary layer thickness?

For a quick order-of-magnitude estimate on a smooth flat plate with laminar behavior, engineers often use

Micro example:

Q24. What causes boundary layer separation?

Separation occurs under an adverse pressure gradient, meaning pressure rises in the flow direction. Near-wall fluid has low momentum, so it cannot overcome that rise, wall shear drops toward zero, and local flow reversal creates a separated region.

Q25. What is the difference between form drag and skin friction drag?

Skin friction drag comes from wall shear stress. Form drag comes from pressure differences driven by separation and wake formation. Streamlining mainly attacks form drag by preventing or delaying separation.

Cavitation, Pumps, And Turbines

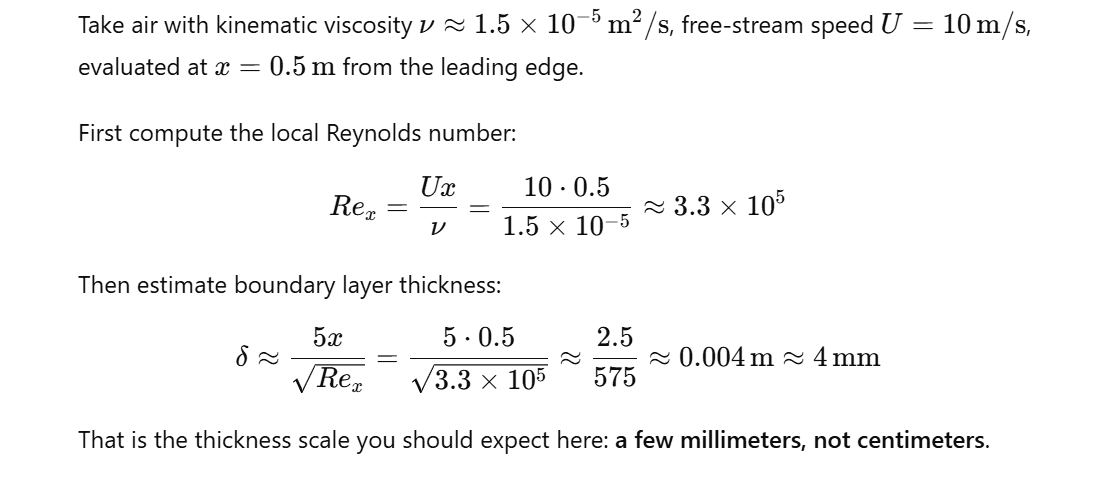

Q26. What is cavitation?

Cavitation is the vapor bubble formation when local static pressure falls to vapor pressure, followed by bubble collapse when pressure recovers. That collapse can pit surfaces and destabilize performance.

Q27. What does cavitation mean in a pump, and what are the symptoms?

In pumps, cavitation often begins at the impeller eye where pressure is lowest. Typical signs include crackling noise, vibration, fluctuating discharge pressure, and an efficiency drop. Damage usually appears as pitting on the inlet side of impeller blades.

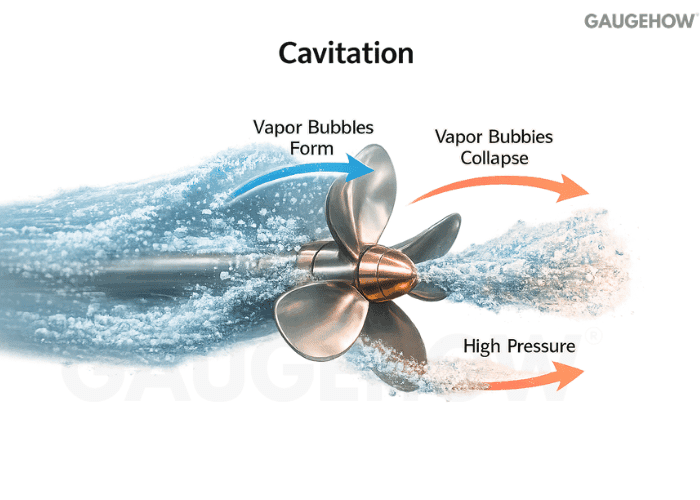

Q28. What is NPSH, and how do you use it to avoid cavitation?

NPSH is the suction pressure margin above vapor pressure, expressed as head. You prevent cavitation by ensuring NPSH available exceeds NPSH required with a comfortable margin.

NPSH available comes from suction pressure head plus velocity head, minus vapor pressure head, and suction line losses.

NPSH required is from the pump curve and often rises with flow rate.

Keep NPSH available above the required, not barely equal, because transients and temperature shifts reduce the margin.

Micro example with round numbers:

Q29. What is a pump head, and how is it different from pressure?

Pump head is the energy added per unit weight, expressed as meters of fluid. Pressure rise is energy per unit volume. They link by

So the same head produces a different pressure rise depending on density.

Q30. What is the difference between a centrifugal pump and a positive displacement pump?

A centrifugal pump is dynamic; it adds energy by increasing fluid momentum with an impeller and converting it to pressure. A positive displacement pump traps and forces a fixed volume forward, so it can generate high pressures at low flows and behaves very differently with system resistance.

Q31. What are the pump affinity laws, and when do engineers use them?

Affinity laws are scaling rules for similar pumps when speed changes.

Micro example: A 10% speed increase gives roughly 10% more flow, 21% more head, and 33% more power demand. That is why motor margin matters.

Q32. What is the specific speed of a pump, and what does it tell you?

Specific speed is a similarity parameter that points to the pump family best suited for a head–flow target. Engineers use it to avoid forcing a radial-style pump into an axial-flow job, or the other way around.

Q33. What is BEP in a pump, and why does it matter?

BEP is the best efficiency point where incidence and hydraulic losses are minimized. Running far from BEP increases vibration, recirculation, heat rise, and seal or bearing stress, even if the pump still “meets the duty.”

Q34. What is the difference between a pump and a turbine?

A pump consumes shaft power to increase fluid energy. A turbine extracts fluid energy to produce shaft power. Same physics, opposite energy direction.

Q35. What is the difference between impulse and reaction turbines?

Impulse turbines convert pressure head to jet velocity first, then extract momentum change on the runner, so pressure across the runner is near atmospheric. Reaction turbines extract energy through both pressure drop and velocity change across the runner, so pressure changes through the blades.

Q36. Where do Pelton, Francis, and Kaplan turbines fit?

Pelton is an impulse and suits high head, low flow. Francis is reactive and fits medium head ranges. Kaplan is a reaction with axial flow and suits low head, high flow applications.

Q37. Why is cavitation also a concern in turbines?

Low-pressure zones can form at runner exits and draft tube regions, especially off-design. Once local pressure approaches vapor pressure, cavitation begins, and erosion plus performance instability follow.

Manometers And Pressure Reading

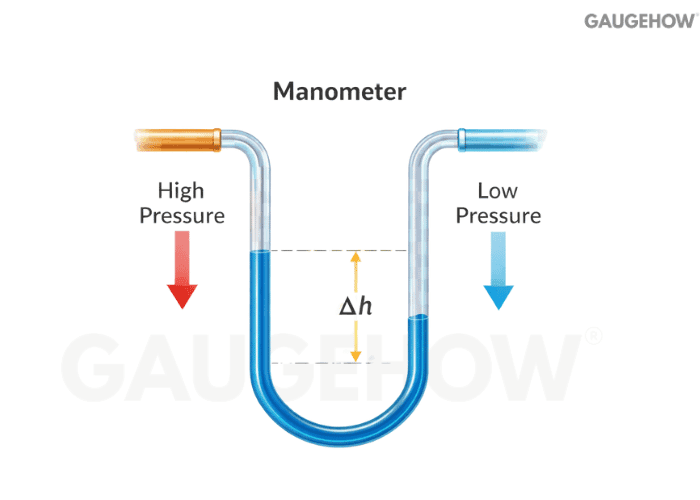

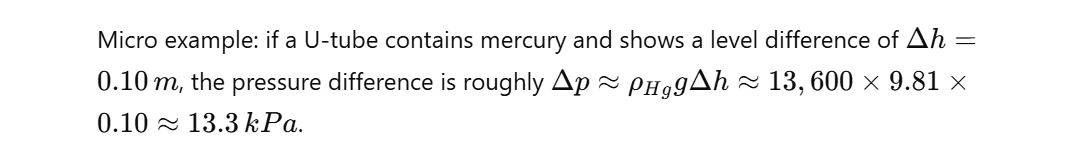

Q38. What does a manometer measure?

A manometer measures pressure difference by balancing it against a known fluid column height. The height difference maps to the pressure difference through the hydrostatic relation.

Q39. How to use a manometer?

Using a manometer is just consistent with hydrostatics, with clear sign control.

Label the two connection points and the manometer fluid(s).

Move through the columns, adding pressure when you go downward and subtracting when you go upward.

If multiple fluids exist, apply ( \rho g \Delta h ) with the correct density for each segment.

Q40. How do you find absolute pressure from gauge pressure?

Absolute pressure equals gauge pressure plus atmospheric pressure. Gauge is referenced to ambient, while absolute is referenced to vacuum, so the conversion is a simple offset.

Conclusion

Fluid mechanics interviews reward clear cause-and-effect thinking, not long derivations. If you can explain how viscosity sets regime through Reynolds number, how continuity and Bernoulli track mass and energy, how friction and K-losses create head loss, and why cavitation is a suction margin problem solved by NPSH, you will sound like someone who can diagnose real flow systems. Keep the micro examples ready, because a clean number check often separates memorized theory from engineering judgment.