Heat Transfer Questions & Answers

Jan 18, 2026

Deepak S Choudhary

🔧 Trusted by 23,000+ Happy Learners

Industry-Ready Skills for Mechanical Engineers

Upskill with 40+ courses in Design/CAD, Simulation, FEA/CFD, Manufacturing, Robotics & Industry 4.0.

Heat transfer problems feel simple until you must pick the right mode, write the right law, and keep sign conventions straight. These 40 Q&As sharpen conduction, convection, radiation, heat exchangers, LMTD, fins, and thermal resistance so you can explain, estimate, and debug real thermal designs fast.

Heat transfer is energy in transit because of a temperature difference. It tells you how fast that energy moves, in what direction, and through which path.

Ever looked at a hot pipe, a cooling fin, or a heat exchanger and wondered which equation is actually the right starting point?

This guide covers conduction, convection, radiation, Fourier’s law, Newton’s law of cooling, heat exchangers, LMTD, fins, thermal resistance networks, and black body ideas, with short answers designed for quick engineering decisions.

When you are unsure which model to start with, anchor on the resistance picture.

Pick the dominant resistance first, not the fanciest equation.

Write the temperature nodes and the heat flow path before doing algebra.

Check units early: W, W/m², and W/m·K never “accidentally” match.

If two mechanisms act in parallel, add heat rates, not resistances.

That habit prevents most wrong turns because the math will follow the physics.

Q1. What exactly is “heat transfer” measuring in engineering terms?

It measures the rate of energy flow driven by a temperature difference. Thermodynamics tells you how much energy can change state, while heat transfer tells you how quickly it moves through real materials and fluids.

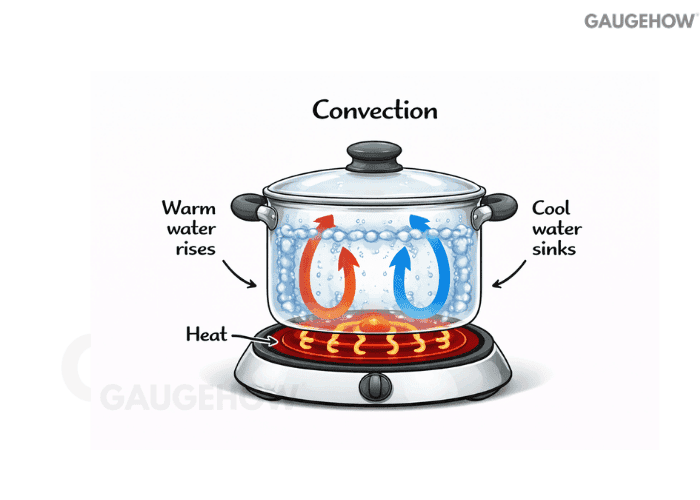

Q2. How do you tell conduction, convection, and radiation apart on a real part?

Conduction is energy diffusion inside a material due to molecular interaction. Convection is energy exchange between a surface and a moving fluid. Radiation is energy exchanged by electromagnetic waves, so it can happen across a vacuum.

Q3. What is the practical meaning of Fourier’s law, beyond the formula?

Fourier’s law says heat flows down the temperature slope, and the slope is the real driver inside solids.

If you steepen the gradient or increase the area, the heat rate rises. If you lower the conductivity or lengthen the path, the heat rate falls.

Q4. Why does Fourier’s law carry a negative sign?

The negative sign enforces direction: heat flows from higher temperature to lower temperature. If temperature increases in the +x direction, the heat flux in +x must be negative because it flows opposite the rise.

Q5. What is heat flux, and why do designers care more about it than total heat rate?

Heat flux is the heat rate per unit area. It is what drives local overheating, coating failure, boiling, and hot spots, even when the total heat rate looks acceptable.

Q6. When can you treat conduction as one-dimensional?

Use 1-D conduction when heat mostly travels in one direction and edge effects are small, typically when the thickness is much smaller than the other dimensions and boundary conditions are fairly uniform across the face.

Q7. What is thermal contact resistance, and when is it not negligible?

Two solids rarely touch over the full apparent area because of surface roughness, waviness, and trapped air. That creates a temperature drop at the interface that can dominate in clamped joints, interface pads, and “metal to metal” contacts with low pressure.

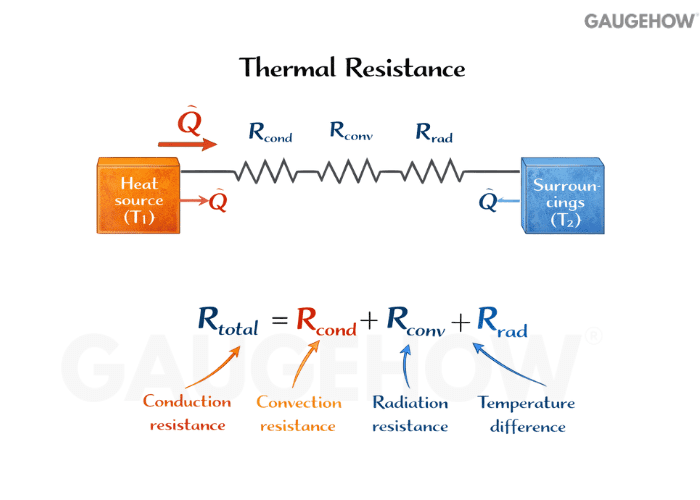

Q8. How do thermal resistance networks make mixed-mode problems easier?

They turn conduction and convection into one common language: temperature drop equals heat rate times resistance.

Once you draw nodes and resistances, series paths add directly, and parallel paths combine like electrical circuits.

Q9. Is thermal resistance the inverse of thermal conductivity?

Not by itself. Conductivity is a material property, while resistance depends on geometry. For a slab, resistance scales with thickness and area,

so only for a fixed geometry does “higher k” reliably mean “lower R.”

Q10. What is thermal resistivity, and how is it used?

Thermal resistivity is 1/k, a property that makes comparisons intuitive when geometry is fixed. It helps when screening materials for the same thickness and area, but it does not replace a full resistance calculation.

Q11. What changes when there is uniform internal heat generation in a solid?

The temperature profile becomes curved because the material is creating heat as well as conducting it. The peak temperature can occur inside the body, and boundary conditions decide how that internally generated heat escapes.

Q12. What is the difference between steady and transient conduction?

Steady conduction means the temperature field does not change with time, even though heat is flowing. Transient conduction means temperatures are still evolving, usually after a step change such as startup, shutdown, or a sudden ambient shift.

Q13. When is a lumped temperature model a safe shortcut?

Use it when the object stays nearly uniform in temperature while it heats or cools. Practically, if internal temperature gradients are small compared to the surface-to-ambient difference, a single-temperature model is reasonable.

Q14. What is the convection coefficient h, and why is it never “just a property”?

h converts a surface-to-fluid temperature difference into a heat rate, but it depends on boundary-layer physics.

Velocity, viscosity, conductivity, geometry, and flow regime all change it, so it varies with operating conditions.

Q15. How do you quickly separate natural convection from forced convection?

If a fan, pump, imposed flow rate, or motion drives the fluid, it is forced convection. If buoyancy from temperature-driven density differences mainly creates the flow, it is natural convection.

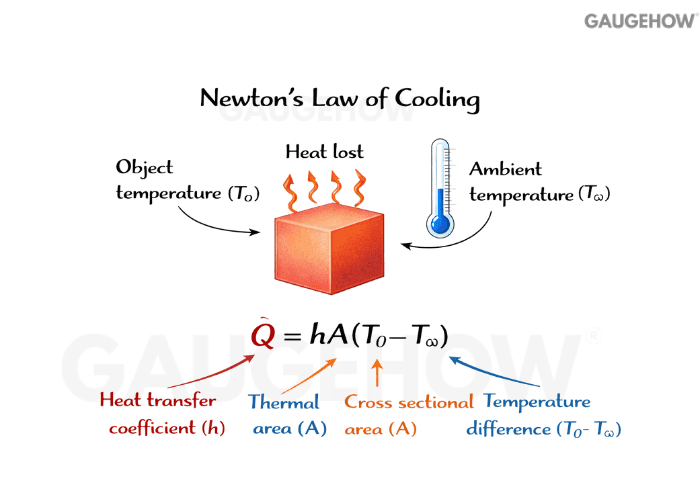

Q16. Is Newton’s law of cooling only for cooling, or can it model heating too?

It models either direction as long as h is approximately constant over the temperature range. The sign of the heat rate flips naturally based on whether the surface is hotter or colder than the surrounding fluid.

Q17. What does the constant k represent in Newton’s cooling equation for temperature vs time?

It is a lumped rate constant that depends on surface area, heat capacity, and the effective heat transfer coefficient. In practice,ce it hides geometry h and thermal mass, which is why you fit it from data rather than “look it up.”

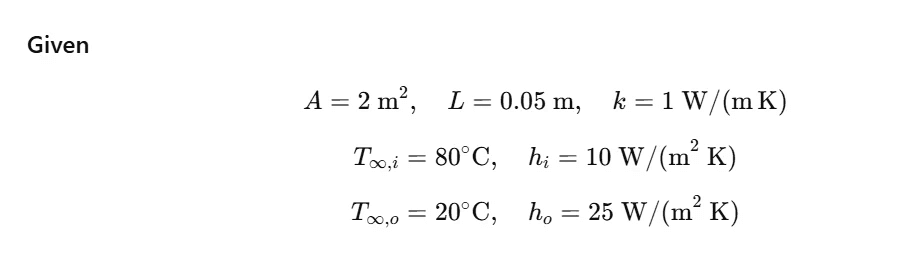

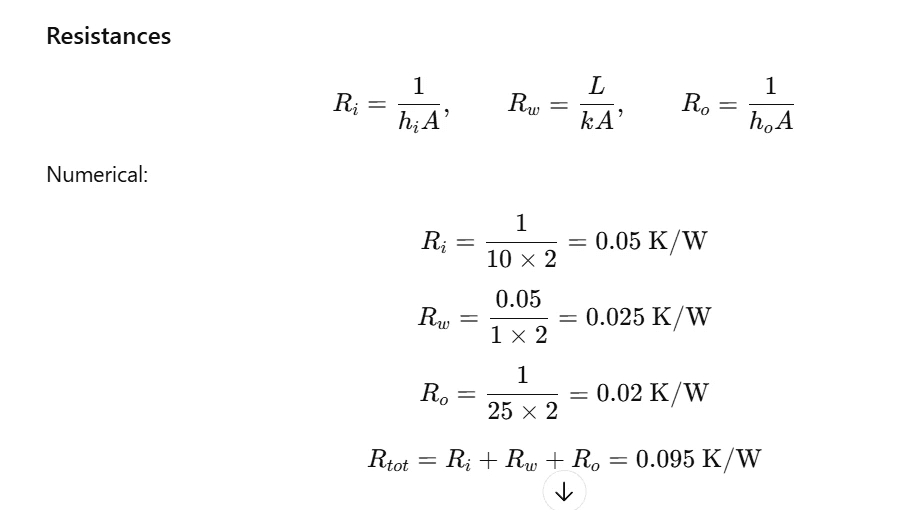

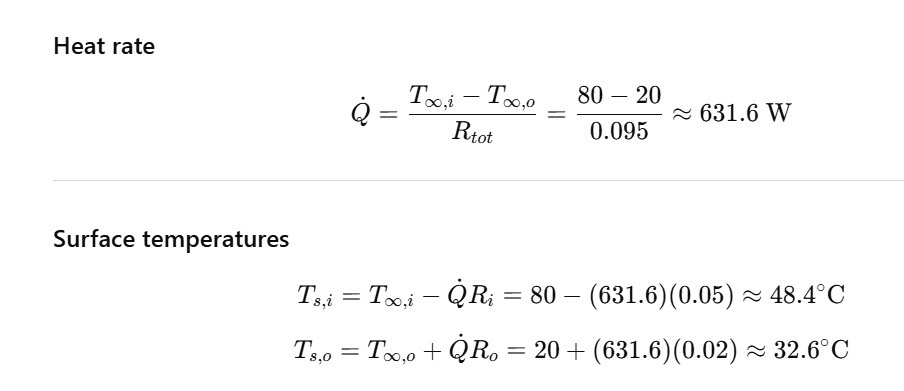

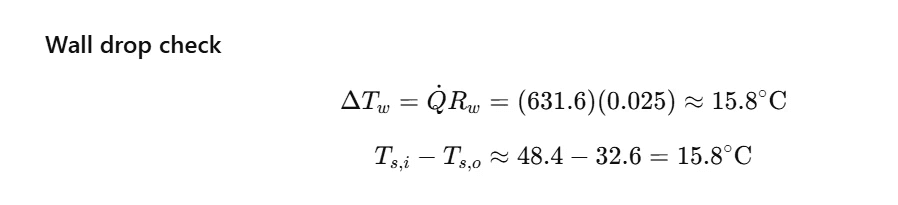

Q18. Worked example: How do you compute heat loss through a wall with inside and outside convection?

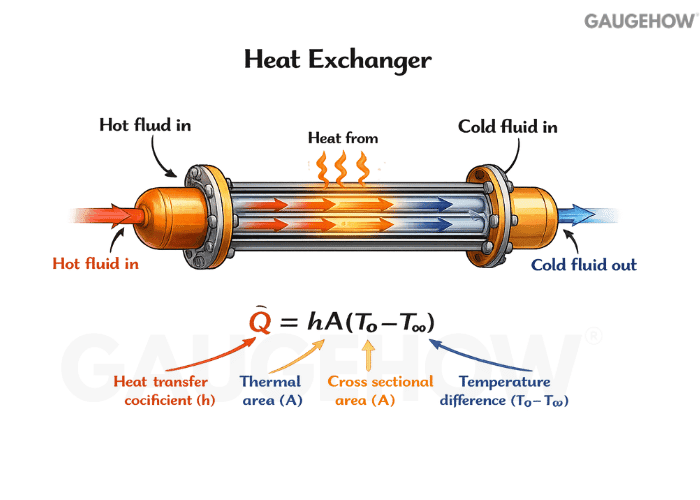

Q19. What is the “overall heat transfer coefficient” U, and what does it buy you?

U packages all resistances between two fluids into one coefficient, so you can write

without tracking every layer each time. It is most useful for heat exchangers and composite walls where conduction and two convective films act together.

Q20. In a heat exchanger, why does counterflow usually outperform parallel flow?

Counterflow maintains a larger temperature driving force over more of the length. That typically increases the mean temperature difference for the same inlet conditions, so you need less area for the same duty.

If your heat-exchanger math feels unstable, it is usually a sign or endpoint issue.

Pair the correct hot-end and cold-end temperatures for each end.

Keep temperature differences positive by defining

consistently.

Verify that the cold stream cannot exit hotter than the hot inlet.

If a log appears, confirm you are not dividing by a negative ratio.

Those checks save time because most LMTD mistakes are bookkeeping, not physics.

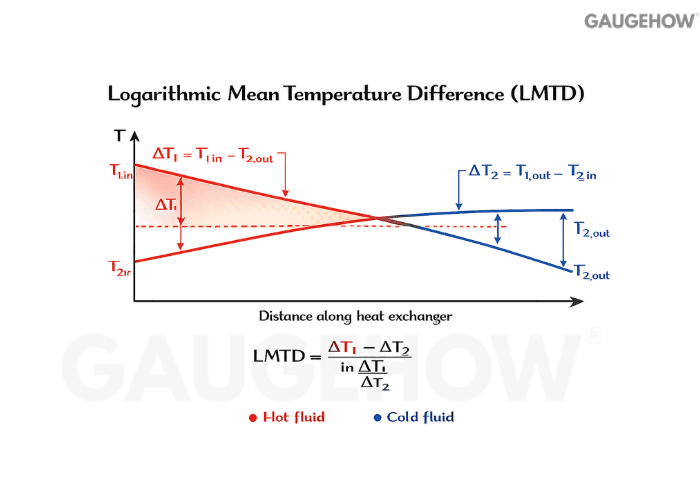

Q21. What is LMTD really averaging, physically?

It is the correct mean temperature driving force for a heat exchanger when the local temperature difference changes along the length. Because that driving force varies nonlinearly with position, a simple arithmetic mean gives the wrong heat rate for the same area.

Q22. Why is LMTD a logarithmic mean, not a linear mean?

Along the exchanger, the differential heat transfer is proportional to the local (\Delta T). When you integrate that relationship with temperatures that change due to energy balance, the math naturally produces a logarithm.

Q23. Tiny example: how do you compute LMTD quickly without getting lost?

Q24. What does it mean if your LMTD comes out negative, and how do you handle it?

It usually means you mixed endpoints or defined a temperature difference with an inconsistent sign. Redefine temperature difference as a positive magnitude at each end using one “hot minus cold” convention, then recompute. If temperature profiles actually cross in a complex arrangement, LMTD alone is not the right tool without the proper correction treatment.

Q25. When is the LMTD method the right choice, and when is it the wrong one?

Use LMTD when both outlet temperatures are known or can be found cleanly from an energy balance, and you wantthe area. If an outlet temperature is unknown and depends strongly on area, effectiveness-based approaches often stay cleaner because they avoid iterative guessing.

Q26. What does heat-exchanger effectiveness measure in plain terms?

It compares the actual heat transfer to the maximum possible heat transfer for the same inlet conditions. It is a performance fraction that stays meaningful even when the temperature driving force shifts with flow arrangement.

Q27. What is the simplest meaning of the overall resistance in a heat exchanger?

It is the sum of the hot-side film resistance, wall conduction resistance, cold-side film resistance, and any fouling terms, all expressed on a common area basis. The biggest term is where the improvement effort pays off.

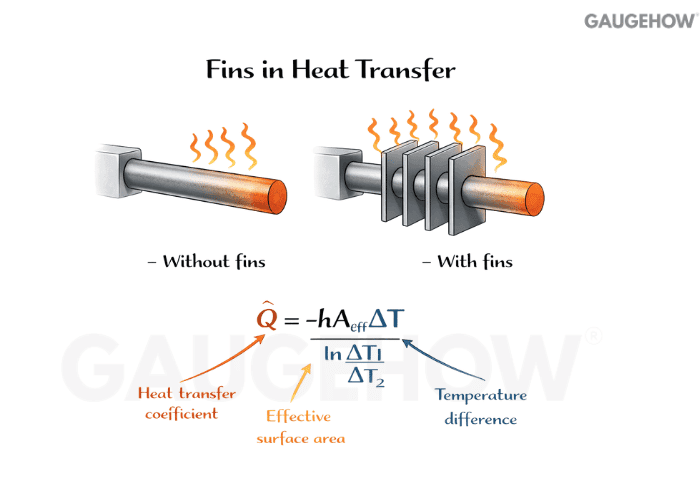

Q28. Why do fins work, and when do they stop being worth it?

Fins work by adding surface area so convection has more area to act on.

They stop being worth it when conduction inside the fin becomes the bottleneck, so the extra area sits near ambient temperature and contributes very little.

Q29. Tiny example: how do you decide if a fin material is conductive enough?

Q30. What is the difference between fin efficiency and fin effectiveness?

Efficiency compares real fin heat transfer to the ideal case where the entire fin is at base temperature. Effectiveness compares heat transfer with the fin to heat transfer from the same base area without the fin, which is the decision metric for whether to add fins at all.

Q31. What is thermal resistance doing for fins specifically?

It makes the fin behave like distributed conduction feeding distributed convection. Once you see that, you stop expecting the whole fin to be equally useful and start designing for a strong root region where most of the heat actually enters the fin.

Q32. What counts as radiation heat transfer, and what does not?

Radiation is energy exchanged by electromagnetic waves between surfaces.

It is not hot air rising, and it is not heat moving through metal, even though all three can happen together around the same component.

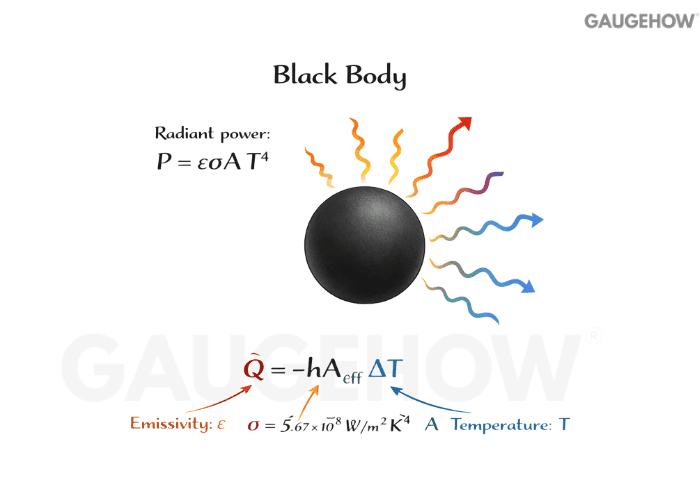

Q33. What is a black body in engineering terms?

A blackbody is an ideal surface that absorbs all incident radiation and emits the maximum possible radiation at a given temperature.

Real surfaces fall below that ideal and are modeled with an emissivity.

Q34. What is emissivity, and why does it change the answer so much?

Emissivity scales how strongly a real surface emits compared to a black body at the same temperature. Because radiative emission increases strongly with temperature, emissivity shifts can swing heat-loss estimates, especially at elevated temperatures.

Q35. What is the view factor, and when can you not ignore it?

The view factor is the geometric fraction of radiation leaving one surface that directly reaches another. You cannot ignore it when surfaces are close, partially facing, or shielded, because geometry can dominate even with high emissivity.

Q36. How do radiation shields reduce heat transfer without cooling anything?

A shield inserts extra radiative resistances by adding additional surfaces in series. If the shield has low emissivity, the net exchange drops sharply even though temperatures can remain high.

Q37. In mixed convection and radiation, how do you decide which dominates?

Estimate both heat rates using the same area and temperature levels. If radiation is comparable or larger, treat them as parallel paths and add heat rates. If one is clearly smaller, you can neglect it, but only after checking the scale.

Q38. Why can adding insulation to a small cylinder sometimes increase heat loss?

On small-radius cylinders, insulation increases conduction resistance but also increases outer surface area, which reduces convection resistance. There is a radius range where the area effect wins initially, so heat loss rises before it eventually falls as insulation thickens.

Q39. What does fouling resistance do to a heat exchanger design?

Fouling adds an extra resistance term that lowers (U) over time, so the same exchanger transfers less heat at the same driving force. Design margin comes from accounting for that resistance up front, not assuming the clean condition holds.

Q40. What are the most common reasons heat-transfer answers look right but are wrong?

Mixing endpoints in LMTD, using the wrong area basis for (U), and quietly changing units are the top offenders. Another frequent miss is treating one mode as dominant when two act in parallel, which underpredicts real heat loss or gain.

Conclusion

Heat transfer becomes predictable once you stop hunting formulas and start drawing the heat-flow path. Choose the dominant resistance, keep signs consistent, and use quick bounds and unit checks. Do that, and conduction, convection, radiation, LMTD, and fins behave like one system instead of separate chapters.