Industrial Automation and Industry 4.0 Questions & Answers

Jan 18, 2026

Deepak S Choudhary

🔧 Trusted by 23,000+ Happy Learners

Industry-Ready Skills for Mechanical Engineers

Upskill with 40+ courses in Design/CAD, Simulation, FEA/CFD, Manufacturing, Robotics & Industry 4.0.

Rapid-fire but practical questions on PLCs, sensors, actuators, robotics, PID control, CNC automation, and industrial automation interview questions. Each answer stays shop-floor realistic, so you can explain what happens in the cabinet, on the machine, and in the data layer. Includes one worked control example and two tiny numeric checks.

Industrial automation is the use of control systems and machines to run a process with repeatable results. Industry 4.0 builds on that by connecting machines, data, and decisions across the factory.

Ever been asked to explain a PLC, a robot, and “smart manufacturing” in the same interview, and felt the answers drift into buzzwords?

This guide covers the full chain, from sensor signals and actuators to feedback control, CNC automation, robotics, and the Industry 4.0 stack that sits above the machines.

Q1. What does “industrial automation” mean in factory terms?

It means a process runs by defined logic rather than constant human intervention. Sensors observe, logic decides, and actuators move energy into the machine.

The goal is consistent output, consistent quality, and predictable cycle time.

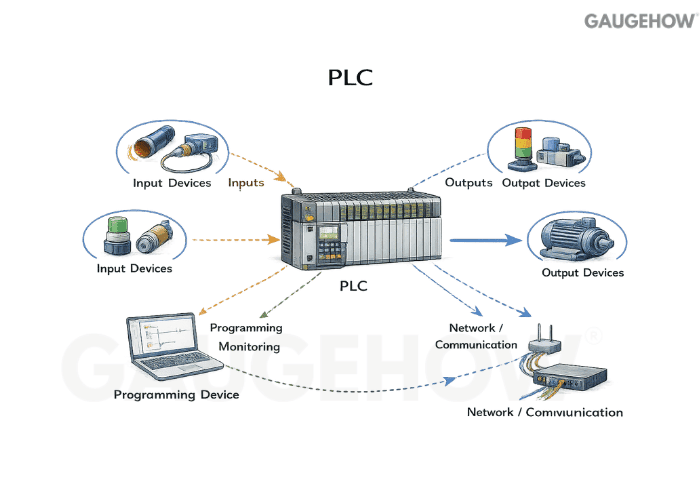

Q2. Why do plants use PLCs instead of wiring everything with relays?

A PLC replaces large relay logic with software plus modular I/O. Changes become program edits instead of rewiring. Troubleshooting is faster because you can see the live status and isolate a fault path quickly.

Q3. How does a PLC actually run a program during production?

Most controllers run a repeating scan

Cause: The PLC needs deterministic decision cycles

Effect: Scan time becomes the reaction speed ceiling

Example: Short pulses can be missed if shorter than the scan plus filtering

That loop time matters because it sets how fast the system can react. If the process changes faster than the scan and the hardware response, you get missed events.

Q4. What are the main building blocks inside a PLC system?

Think of it as power, processor, memory, and I/O with communication modules around it.

The I/O is the interface to the real world, while the CPU executes control logic. Communication modules move data to drives, HMIs, SCADA, and other controllers.

Q5. What is the practical difference between digital and analog I/O?

Digital I/O is two-state, like a limit switch or a solenoid coil command. Analog I/O represents a range, like pressure, temperature, speed demand, or valve position. Digital is about events, analog is about control quality.

Q6. How do sensor signals become usable logic inside the PLC?

Input modules condition the signal so the CPU can use it reliably. Digital inputs convert a voltage or current threshold into a 0 or 1. Analog inputs convert a continuous signal into a number, then your program scales it into engineering units.

Q7. How do you scale an analog sensor into engineering units?

You map the raw input range to a physical range, then apply linear scaling in the controller.

Micro example: A 4–20 mA pressure transmitter is rated 0–100 bar. At 12 mA, the fraction of span is (12 − 4) / 16 = 0.5, so the pressure is 50 bar.

Q8. What causes “noisy” readings, and how do you reduce them without guessing?

Noise is usually a mix of electrical coupling, grounding mistakes, unstable supply, poor shielding, and process vibration that the sensor faithfully picks up.

Fixing it starts by separating what is electrical from what is truly mechanical.

Check the grounding and shielding strategy first, because a bad return path makes every sensor look bad.

Slow down the measurement with filtering only after you confirm the wiring is sane.

Verify sampling and scan timing, because fast jitter can be created by the measurement chain itself.

Inspect mounting and vibration, because some “noise” is real motion.

A clean signal gives you stable control, and stable control prevents false trips and scrap.

Q9. What’s the difference between a sensor, a switch, and a transmitter?

A sensor is the sensing element that reacts to a physical change. A switch outputs a discrete state based on a threshold. A transmitter outputs a scaled signal that represents a range, so you can do real control, trending, and alarms.

Q10. What do people mean by NPN vs PNP sensors in automation wiring?

It’s about how the sensor drives the input. One style sources current to the input, the other sinks current from it. Matching sensor type to the input module wiring scheme avoids “it works on the bench but not on the machine” failures.

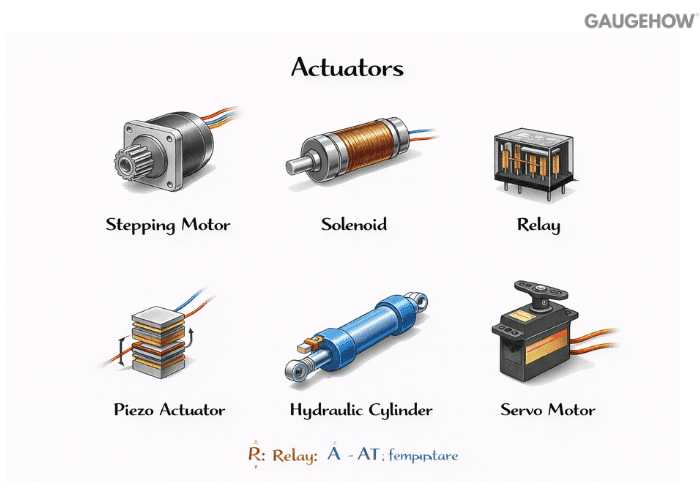

Q11. What is an actuator, in simple control language?

An actuator turns a control command into physical action. It can move, clamp, rotate, open, close, heat, or regulate flow.

If sensors are the eyes and ears, actuators are the hands that change the process.

Q12. How do you choose between pneumatic, hydraulic, and electric actuation?

Pneumatics are fast and simple for on-off motion and moderate force. Hydraulics win when force density and stiffness matter. Electric actuation wins on precision, programmability, and cleanliness, especially when motion profiles matter.

Q13. How can you estimate cylinder force quickly during selection?

Force is pressure times piston area, minus losses you should expect in real hardware.

Micro example 2: A 50 mm bore cylinder at 6 bar has an area ≈ of 0.00196 m², so an ideal force ≈ of 600,000 Pa × 0.00196 ≈ 1,180 N before friction and regulator drop.

Q14. When would you use a solenoid valve versus a proportional valve?

A solenoid valve is best for a discrete on-off flow. A proportional valve is for controlled flow or pressure when you need smooth regulation. Choosing the wrong one shows up as hunting, overshoot, or slow settling.

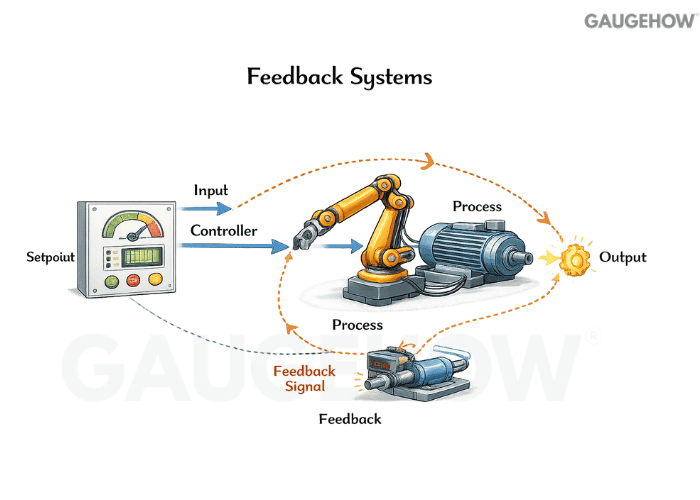

Q15. What is the difference between open-loop and closed-loop control?

Open-loop control issues a command and assumes the outcome happens. Closed-loop control measures the result and corrects the command based on the error. Closed-loop is what you use when load, friction, and disturbances exist, which is most factories.

Q16. What does “feedback” mean in an automation system?

Feedback is the measured result coming back into the decision logic.

It tells the controller whether the process followed the command. Without feedback, you can run, but you cannot prove you ran correctly.

Q17. How do positive and negative feedback differ in control behavior?

Negative feedback counters the error, pushing the process toward a target. Positive feedback reinforces the change, pushing the process further in the same direction. Positive feedback can be useful in latches or oscillators, but it can destabilize a control loop if used in regulation.

Q18. Why do most industrial control loops use negative feedback?

Because it naturally fights disturbances. A load change, a supply fluctuation, or wear shows up as an error, and the loop corrects it. That gives repeatable output even when the machine is not “perfect.”

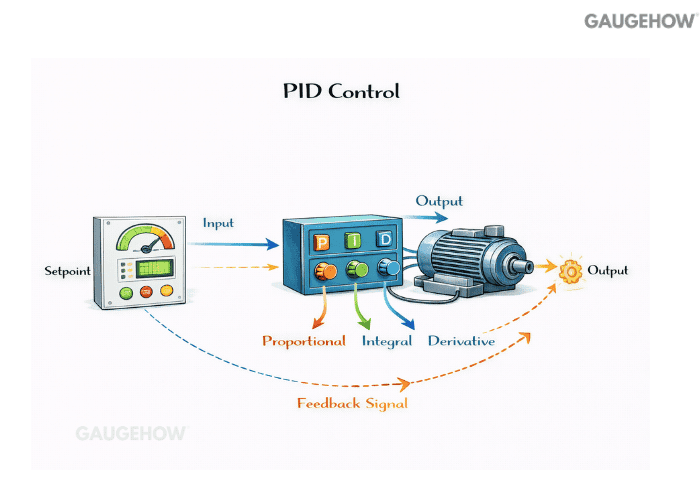

Q19. What is a PID controller, without a math-heavy explanation?

It is a rule that adjusts an output based on error now, error accumulated over time, and error trend.

The goal is to reach the setpoint quickly while staying stable. It is used everywhere from temperature control to speed and tension control.

Q20. What do P, I, and D actions change in a real response?

Proportional reacts immediately, so it speeds up correction but can overshoot if too aggressive. Integral removes a steady offset, but it can cause slow oscillation if too strong. Derivative damps rapid change, but it amplifies noise if the measurement is dirty.

Q21. What does “PID” expand to, and why does that naming matter?

It stands for proportional, integral, and derivative. The naming matters because it reminds you that the controller is balancing present error, accumulated error, and changing error. That mental model helps you tune logically instead of randomly.

Q22. How do you tune a PID on a real machine when you do not have a model?

Start by stabilizing the measurement and actuator response, because tuning cannot fix noise and stiction. Increase proportional gain until you get a fast response that is still stable. Add integral slowly until the steady offset disappears, then add a small amount of derivative only if you need damping and the signal is clean.

Q23. How do you calculate a PID output for one control update?

Here is one worked example using a discrete update, so the logic is obvious.

Worked example: Temperature setpoint is 80 °C, measured is 75 °C, so error e = 5. The previous error was 3. Sample time is 1 s. Choose Kp = 2, Ki = 0.5 per second, Kd = 1 second.

If the accumulated error sum was 10, it becomes 15 after adding the new error. The proportional term is 2 × 5 = 10. The integral term is 0.5 × 15 = 7.5.

The derivative term uses the change in error, so (5 − 3) / 1 = 2, giving 1 × 2 = 2. Total controller output = 10 + 7.5 + 2 = 19.5 in whatever output units your actuator uses.

Q24. What is “integral windup,” and what does it look like on a machine?

Windup happens when the actuator is saturated, but the integral term keeps accumulating. When the actuator finally comes back into range, the stored integral drives a large overshoot. The cure is limiting or back-calculating the integral when the output hits limits.

Q25. Where does a drive fit, and what control should stay in the drive versus the PLC?

A drive controls motor power and often closes the fast inner loop for speed or torque. The PLC should handle sequencing, interlocks, and slower supervisory control. Putting a high-speed motion loop in a slow scan controller usually creates lag and instability.

Q26. What role does an encoder play in motion control?

An encoder measures position or speed so the controller can correct motion. Without it, you can command a motor, but you cannot confirm it reached the demanded position under load. Closed-loop motion is basically “measure, compare, correct” at high speed.

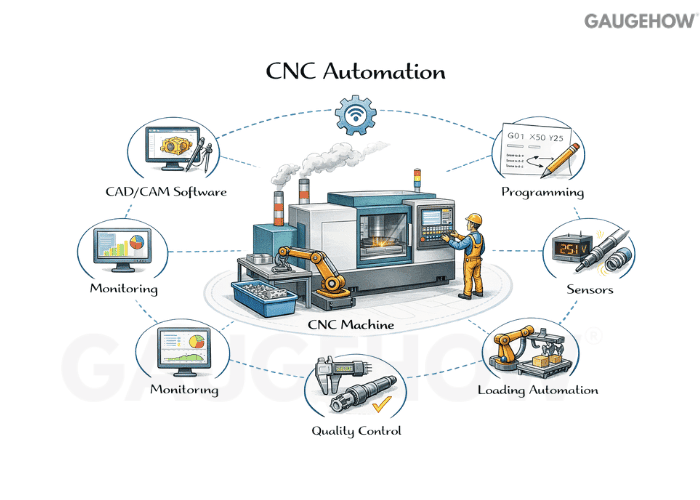

Q27. What is CNC automation beyond just running a CNC program?

It is everything that reduces manual handling and variability around the machine.

That includes tool changing, probing, pallet changing, part loading, and automated inspection. The aim is fewer stoppages and more predictable throughput.

Q28. What must be engineered carefully when adding a robot to a CNC cell?

The handshake between the robot, the machine, and the safety system must be deterministic. Door interlocks, chuck status, cycle complete, and fault resets need clean logic. The fastest robot in the world does not help if the cell deadlocks on a missed signal.

Q29: Automation levels from field devices to MES/ERP (L0–L4).

Level | What It Controls | Typical Signals | Typical Failure Mode |

L0 | Sensors/actuators | 24 V DI/DO, 4–20 mA, encoder pulses | noise, wiring faults, mis-scaling |

L1 | Machine logic | PLC interlocks, sequences, and motion enable | missed handshakes, scan too slow |

L2 | Cell supervision | HMI/SCADA alarms, recipes, trends | alarm floods, wrong permissions |

L3 | Execution layer | MES orders, genealogy, OEE | Bad master data, wrong routing |

L4 | Business planning | ERP schedule, inventory, planning | mismatch between plan and capacity |

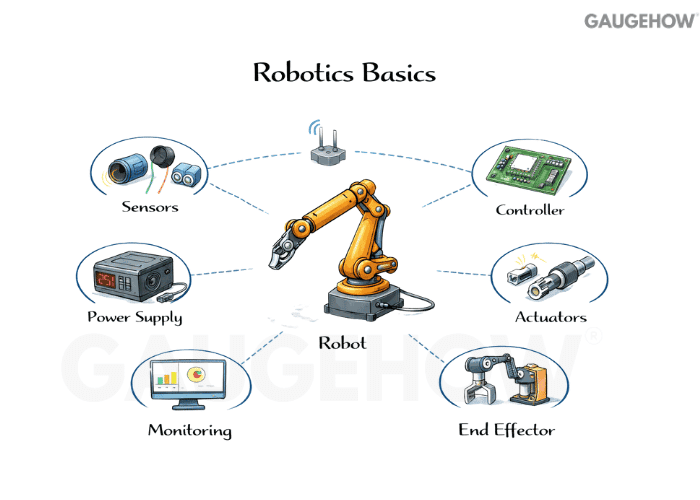

Q30. What makes something a robot rather than a simple automated mechanism?

A robot typically has programmable motion with multiple degrees of freedom and repeatable paths.

A fixed mechanism repeats one motion with minimal flexibility. Flexibility is the real reason robots appear in modern cells.

Q31. Which robot specs actually matter when deciding if it fits the job?

Payload, reach, repeatability, and cycle time are the practical ones. Payload is not only the part weight but also the gripper and torque effects at full reach. Repeatability matters more than raw accuracy for many pick-and-place tasks.

Q32. How do collaborative robots differ from industrial robots in real production?

Collaborative robots are designed to limit force and speed so they can work near people under defined conditions. Industrial robots prioritize speed and payload, and usually require separation and guarding. The choice is a safety and throughput trade, not a marketing preference.

Q33. What is a safety PLC, and why isn’t safety just “another program”?

A safety PLC is designed for validated safety functions with controlled failure behavior. Safety logic must be deterministic, testable, and resistant to single faults. Treating safety as normal control logic leads to unsafe assumptions and hard-to-audit systems.

Q34. How do you troubleshoot an automated line that suddenly stops?

Start with what the system believes is unsafe or incomplete, then verify it in the field.

“Order of attack: safety chain → power/air → I/O truth → handshake → motion permissives.”

Check E-stops, guards, and safety chain status before chasing process logic. After that, confirm I/O states, look for missing handshakes, and isolate whether the stop is command-side, sensor-side, or actuator-side.

Q35. How do SCADA and MES differ, and why do both exist?

SCADA is mainly about monitoring and supervisory control, with alarms, trends, and operator interaction. MES sits closer to production management: tracking orders, genealogy, quality records, and performance. One watches and supervises, the other coordinates production execution.

Q36. How does data move in a digital twin?

It moves from:-

“machine/PLC → edge device/gateway → historian/time-series store → SCADA/MES/analytics”.

A digital twin is one consumer of that pipeline when it stays synced to real signals.

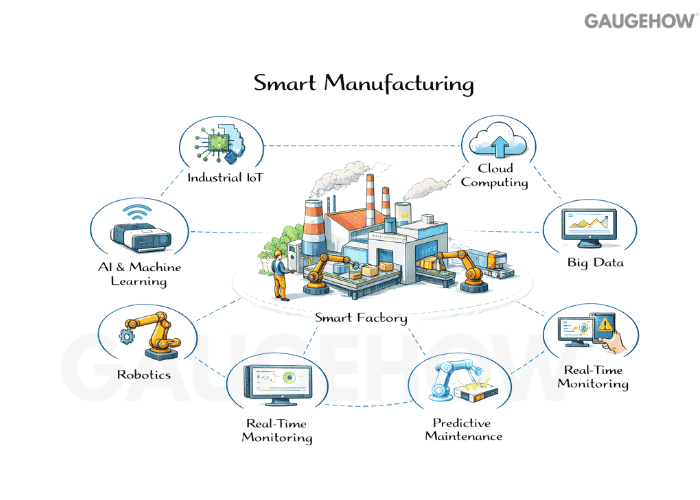

Q37. What does “smart manufacturing” mean, beyond automation?

Smart manufacturing uses data feedback to improve decisions across the plant, not just inside one machine.

It connects condition, quality, and throughput into actionable signals. A smart plant not only runs, it learns where it loses time and why.

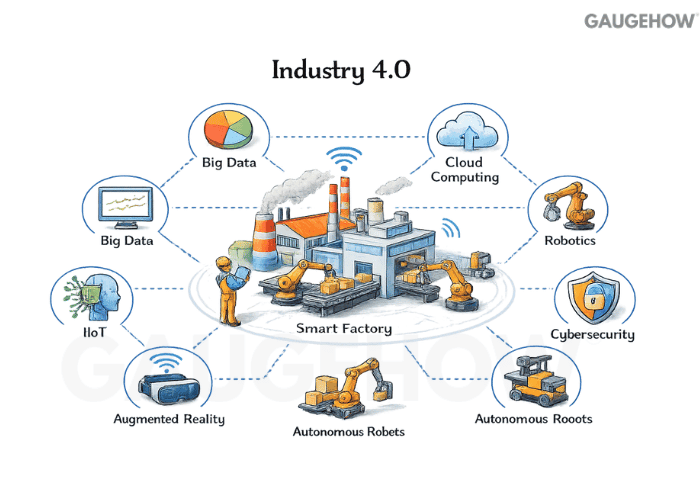

Q38. How would you define Industry 4.0 simply?

Industry 4.0 is the move from isolated automation to connected, data-driven production.

What changes: Decisions become faster, and losses become visible

How: Instrumentation + context + feedback across assets

One concrete outcome: Fewer hidden micro-stops / faster root cause isolation

Connectivity is the differentiator, not the existence of automation itself.

Q39. What is the OT versus IT boundary, and why does it matter for Industry 4.0?

OT is the equipment and control world where availability and safety dominate. IT is the business and data world where confidentiality and scalability dominate. Joining them creates value, but it also expands the cyber risk surface, so segmentation and access control become engineering requirements.

Q40. How do you start Industry 4.0 in a practical way that actually sticks?

Start small, pick a measurable pain point, and build a repeatable pattern before scaling across lines.

Choose one use case tied to downtime, scrap, or energy, not “digitization” as a goal.

Instrument and label data properly, because dirty tags create fake insights

Keep the first loop closed locally, then expose summaries upward

Standardize naming, alarms, and ownership so the system survives staffing changes

Once the first project pays back, you expand with confidence instead of spreading half-built pilots everywhere.

Conclusion

Automation skill is the ability to explain the chain from measurement to motion, and from motion to outcomes. Industry 4.0 skill is the ability to connect that chain to data, decisions, and scale. If you can speak clearly about signals, loops, safety, and integration, you will sound like someone who has actually run a factory system.