Common Manufacturing Processes Interview Questions

Jan 18, 2026

Deepak S Choudhary

🔧 Trusted by 23,000+ Happy Learners

Industry-Ready Skills for Mechanical Engineers

Upskill with 40+ courses in Design/CAD, Simulation, FEA/CFD, Manufacturing, Robotics & Industry 4.0.

Manufacturing processes explain how raw material becomes a finished part through casting, forming, machining, joining, and heat treatment. This guide covers casting vs forging, machining and CNC basics, surface finish and Ra, tolerances, annealing and quenching, welding vs brazing vs soldering, jigs and fixtures, and lean manufacturing, with interview-ready answers focused on when and why each is used.

Manufacturing processes are the practical methods used to shape a part, control its dimensions, and lock in properties through casting, forming, machining, joining, and heat treatment. In simple terms, they turn raw stock into a functional component with predictable quality.

Ever looked at a drawing and wondered why the shop picked forging over casting, or why a feature that looks simple on CAD becomes expensive on the machine?

This guide answers those selection questions in interview-ready form across casting vs forging, machining and CNC basics, surface finish and Ra, tolerances, annealing and quenching, welding vs brazing vs soldering, jigs and fixtures, and lean manufacturing, with short answers focused on when and why each process is used.

Casting & Forming

Q1. What does “forged” mean in manufacturing?

In practice, “forged” means the shape came from plastic deformation under compressive force, not from pouring molten metal. That grain flow alignment is why forged parts often carry better toughness and fatigue resistance for the same alloy.

Q2. When do you choose forging?

You pick it when load-bearing integrity matters more than near-net complexity. On the floor, forging is the default for shafts, hooks, connecting rods, and anything that sees shock or cyclic loads.

Q3. When is casting the right choice?

Shops use casting when geometry is complex, internal cavities are needed, or near-net shape reduces machining time. From a cost standpoint, casting can win hard when the alternative is heavy hog-out machining.

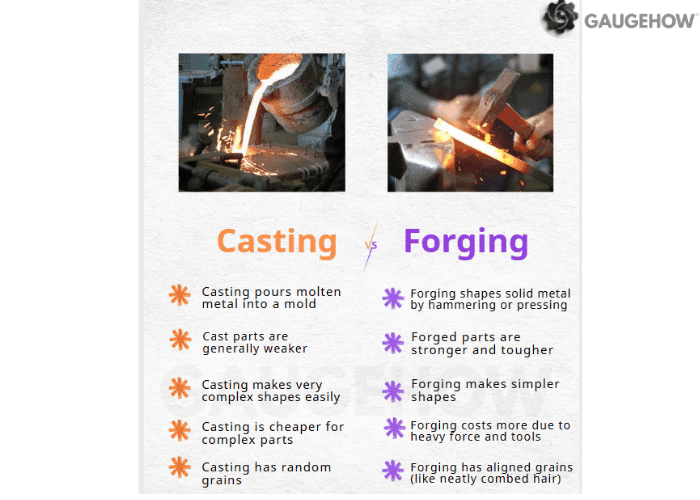

Q4. Casting vs forging: how do you decide fast in an interview?

The quick rule is geometry versus integrity: casting wins on shape freedom, forging wins on load-path reliability.

You use this when you need a quick selection lens:

• Choose casting for housings, pump bodies, and shapes with cavities or bosses that would be expensive to cut.

• Choose forging for safety-critical load-bearing parts where fatigue or impact is the driver.

• If porosity risk or fatigue life is the constraint, forging plus controlled machining is usually safer.

From a production standpoint, volume and tooling also matter because forging dies cost more, while casting tooling ranges from cheap sand tooling to expensive die casting tooling.

Q5. Which casting processes are common, and why do they exist?

For production, the driver is volume and detail. Sand casting fits low to medium volumes and large parts, die casting targets high volume and fast cycles, and investment casting is chosen when fine detail and thin features must be near-net.

Q6. What are common casting defects, and what controls them first?

From a quality standpoint, most defects trace back to filling, feeding, gas, and melt cleanliness. The failure mode to watch is porosity or shrinkage hiding inside a “good-looking” part.

Keep controls practical and first-order:

• Porosity: reduce turbulence, control mold moisture, and improve degassing and venting.

• Shrinkage cavities: fix feeding with risers, chills, and directional solidification.

• Cold shuts and misruns: improve gating, increase metal temperature, and avoid thin, long flow paths.

• Inclusions: tighten melt cleaning, filtering, and slag removal discipline.

On the floor, gating and riser choices are the fastest levers because they change flow behavior and solidification, not just inspection results.

Q7. Where does extrusion make the most sense?

You pick extrusion when the cross-section is constant, and you want long lengths efficiently. It dominates aluminum profiles like frames, rails, heat sinks, and structural members.

Q8. Hot working vs cold working: what changes in the material?

The quick rule is recrystallization: hot working stays ductile because grains reform during deformation, while cold working raises strength by strain hardening. From a failure standpoint, cold work can leave residual stress, so cracking and distortion can show up later unless you plan stress relief.

Machining & CNC

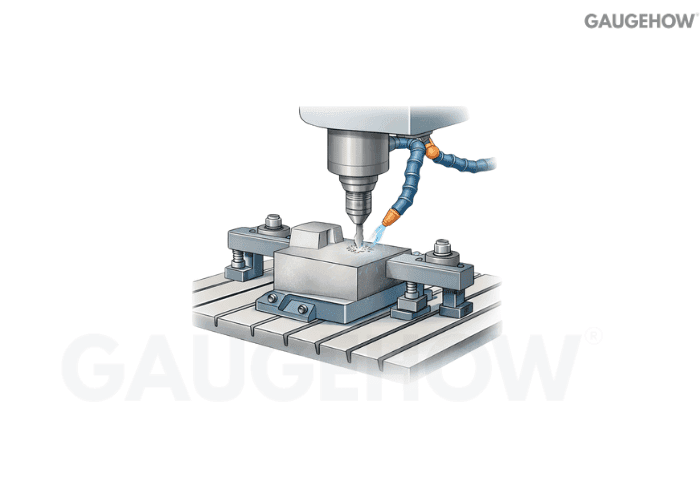

Q9. When do you choose machining over a near-net process?

You choose it when tolerance, true position, or surface function is the driver. On the floor, machining is the “control step” that makes the part match the drawing reliably.

Q10. Machining vs manufacturing: what’s the difference?

Manufacturing is the umbrella, and machining is one method inside it. Shops use machining specifically for material removal to hit dimensions and finish that other processes cannot consistently achieve.

Q11. What does a machine shop do beyond “cutting metal”?

From a production standpoint, it is a repeatability factory. A machine shop plans processes, holds setups, controls offsets, inspects parts, and keeps variation under control across batches.

Q12. What is machine tooling, and why do interviewers ask it?

On the floor, tooling means cutters, holders, fixtures, gauges, and special tools that make production stable. Interviewers ask because tooling choice drives cycle time, scrap rate, and whether tolerance is even achievable.

Q13. Turning vs milling: how do you separate them quickly?

The quick rule is what spins: turning spins the workpiece, milling spins the cutter. You pick turning for concentric features and diameters, and milling for flats, pockets, slots, and complex surfaces.

Q14. What machining parameters control results the most?

For production, the driver is speed, feed, and depth of cut. Those three control forces, heat, chatter, tool life, and finish, more than almost anything else.

Q15. Feed, speed, depth of cut: what do you adjust first when things go wrong?

From a quality standpoint, you adjust the parameter tied to the symptom, not all three at once. The failure mode to watch is chatter, because it destroys finish and tool life together.

Use a clean adjustment order:

• If the finish is poor, drop feed first, then check the tool edge condition and rigidity.

• If tool life is low, reduce speed or improve cooling and chip evacuation.

• If chatter appears, shorten overhang, improve clamping, or shift depth of cut and RPM away from resonance.

On the floor, rigidity and workholding usually decide the outcome before “better inserts” do.

Q16. What is CNC equipment, and what makes it different from manual machines?

Shops use CNC equipment when repeatability and throughput matter.

The quick rule is that CNC gives you consistent motion plus offset control, which is how you hold tolerance over many parts.

Q17. What does CNC do in one line?

On the floor, it converts a program into controlled axis motion and machine actions so parts come out consistently at the required tolerance and cycle time.

Q18. How does a CNC machine work at a high level?

In practice, the controller reads the program, drives servo axes, and applies work and tool offsets while managing spindle and coolant commands. From a quality standpoint, the setup defines whether the code matches the part coordinate system.

Q19. CNC router vs CNC mill: When do you use a router?

You pick a CNC router for sheet materials and lower cutting forces, like wood, plastics, and composites. For metals and tight tolerance work, the driver is rigidity, so a CNC mill is the safer choice.

Q20. What is CNC programming in practical terms?

The quick rule is a safe, repeatable toolpath: define motions, speeds, feeds, tool calls, and clearance moves without collisions. For production, good programming also minimizes tool changes and avoids unstable cuts.

Q21. G-code vs M-code: what’s the difference, with examples?

On the floor, G-codes shape the geometry through motion, while M-codes switch machine functions. The practical constraint is dialect differences between controllers, so you always validate on the target machine.

Common examples:

• G01: linear feed move for controlled cutting paths.

• G02 / G03: circular interpolation for arcs and radii.

• M03 / M04: spindle start, clockwise or counterclockwise.

• M08: coolant on for heat and chip control.

From a quality standpoint, wrong M and offset discipline cause scrap faster than imperfect feed tuning.

Q22. Why do work offsets and tool offsets matter so much?

You pick offsets because the machine has to “know” where the part zero and tool geometry are. The failure mode to watch is a correct program with a wrong offset, because it looks fine until it crashes or scraps the first part.

Q23. What is a clean first-off CNC setup routine?

Shops use a safe prove-out: run reduced feed, validate tool lengths, confirm work zero, then measure the first part and adjust offsets. From a production standpoint, that sequence prevents repeatable mistakes at full speed.

Surface Finish & Tolerances

Q24. What is finishing in manufacturing, and why does it cost money?

In practice, finishing is the set of operations that improve surface, appearance, fit, or performance after shaping, like grinding, polishing, deburring, coating, or plating. You pay for it because it adds time, tooling, inspection, and sometimes rework risk if the finish step shifts dimensions.

Q25. How do you measure a surface finish in a shop?

From a quality standpoint, a profilometer is the standard for Ra and related roughness values. The practical constraint is the measurement setup because direction, cutoff, and filtering can change the number.

Keep it controlled:

• Use a stylus profilometer when the drawing specifies Ra or another roughness parameter.

• Measure in the functional direction because the lay direction changes readings.

• Keep cutoff length and filter settings consistent so results are comparable.

On the floor, visual comparators are fine for quick checks, but functional surfaces need instrumented measurement.

Q26. What is surface roughness, and what does Ra mean?

The quick rule is texture: roughness is the fine-scale pattern left by manufacturing. Ra is the average absolute deviation of the surface profile from the mean line over a sampling length, which is why it is widely used and easy to specify.

Q27. How do you calculate the Ra conceptually?

In practice, Ra is the mean of absolute profile height deviations from the centerline over the evaluation length. From a quality standpoint, Ra can miss isolated deep valleys or sharp peaks, so critical sealing or fatigue surfaces may need additional parameters.

Q28. What is tolerance, and why is it not just “allowed error”?

On the floor, tolerance is a design control that protects assembly and function while keeping the part manufacturable. The failure mode to watch is a stack-up problem where every part is “in tolerance,” but the assembly still fails.

Q29. Tolerance vs fit vs GD&T: what is the practical distinction?

The quick rule is size versus geometry: tolerance sets size limits, fit defines assembly behavior, and GD&T controls geometric requirements like position and runout. For production, GD&T is often what prevents hidden functional failures, even when size is correct.

Heat Treatment

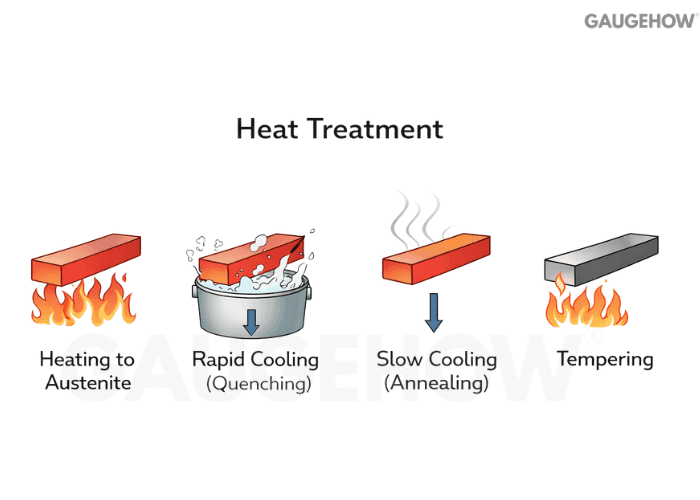

Q30. Why do shops use annealing?

You pick annealing to soften material, relieve residual stress, and recover ductility. From a machining standpoint, it can stabilize cutting and reduce tool wear before final finishing.

Q31. What does “annealed” mean on a callout?

On the floor, it means the material is in a softened, stress-relieved condition relative to a hardened state. The practical impact is improved formability and reduced crack risk during secondary operations.

Q32. What does “quench” mean in heat treatment?

The quick rule is rapid cooling to lock in a harder structure in steels. The practical constraint is distortion because fast cooling creates gradients and transformation strain.

Q33. Why do parts distort after quenching?

From a failure standpoint, uneven section thickness, sharp transitions, and asymmetric geometry warp under thermal gradients and phase change strain. Shops manage this using controlled quench severity, fixtures where appropriate, and design rules that avoid sudden thickness jumps.

Q34. Annealing vs normalizing vs tempering: how do you separate them quickly?

The quick rule is intent: annealing targets softness and stress relief, normalizing targets uniform structure and grain refinement, and tempering reduces brittleness after hardening. For production, the route must meet properties without unacceptable distortion or cracking.

Q35. How do you choose a heat treatment route for a steel component?

Shops use the required property as the starting point, then pick a route that hits it with manageable risk. From a quality standpoint, thin and complex parts often need distortion-aware planning, so heat treat timing relative to machining matters.

Joining Processes

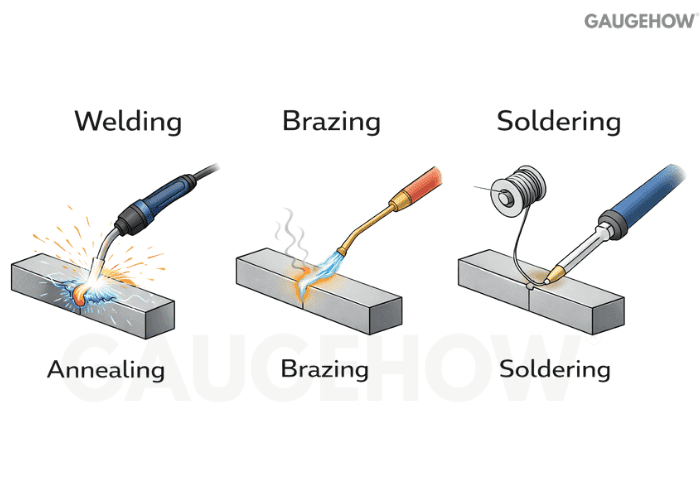

Q36. Welding vs brazing vs soldering: when do you use each?

The quick rule is heat input and base-metal melting: welding melts base metal for strength, brazing and soldering melt only filler for lower distortion.

The practical constraint is joint cleanliness and fit-up because brazing and soldering are sensitive to clearance and contamination.

Selection logic stays simple:

• Use welding for structural joints where strength and fatigue matter.

• Use brazing for dissimilar metals or thin parts where distortion control is critical.

• Use soldering for low-temperature joins, electronics, and light-duty sealing.

From a production standpoint, process choice is as much about distortion and rework risk as it is about ultimate strength.

Q37. MIG vs TIG: how do you justify the choice?

Shops use MIG when speed and deposition rate matter, and TIG when control and quality on thin sections matter. From a quality standpoint, TIG is often preferred for critical root control and clean weld appearance.

Q38. Brazing vs welding in one interview line?

The quick rule is fusion: welding fuses the base metals for higher strength, while brazing bonds with a filler at a lower temperature to reduce distortion and join dissimilar materials.

Jigs & Fixtures

Q39. What is a jig in manufacturing?

On the floor, a jig locates the part and guides the tool, commonly in drilling and reaming. The practical driver is repeatability without relying on operator skill for alignment.

Q40. Jig vs fixture: what is the difference that matters?

The quick rule is guidance: a fixture locates and clamps, but does not guide the tool, while a jig also guides the tool. From a quality standpoint, stable locating often follows 3-2-1, so you constrain the part without over-constraint and induced stress.

Lean Manufacturing

Q41. What is JIT production, and what must be true for it to work?

In practice, Just-in-Time means producing and replenishing only what is needed, when it is needed, in the amount needed. The constraint is stability because JIT collapses if setups are slow, quality is unreliable, or suppliers and scheduling are inconsistent.

Q42. What is lean manufacturing, and when does it actually help on the shop floor?

Shops use lean to reduce waste while protecting flow, quality, and delivery.

The driver is measurable friction, like long changeovers, excess WIP, rework loops, and unstable schedules.

Use tools with constraints in mind:

• Apply 5S and visual controls when searching and motion waste dominate daily work.

• Apply Kanban when WIP and waiting are high, and replenishment can be controlled.

• Apply JIT only when changeover time, quality, and supplier reliability are stable enough to support it.

• Use value stream mapping whenthe lead time is long, and the bottleneck is unclear.

From a production standpoint, lean works when it is tied to hard metrics like lead time, WIP, first-pass yield, and changeover minutes, not slogans.

Conclusion

Manufacturing processes are never just “ways to make a shape.” They are decision systems that trade geometry, properties, tolerance, finish, lead time, and risk against cost and throughput. Casting buys complexity, forging buys integrity, machining and CNC buy dimensional control, heat treatment locks in properties but can introduce distortion, and joining methods balance strength against heat input and fit-up discipline.

On the shop floor, the best engineers win by choosing the process that protects the function with the least variation, then proving it with offsets, inspection, and repeatable setups. If you can explain the “why” behind each selection in one clean line, you are already interview-ready.